“Sandy … It’s Ian.”

Twenty years pass and children become adults. They grow facial hair and start wearing glasses. Their voices change. That’s what they do, Sandy told herself, and if you miss the process, you miss the process. There’s no going back.

“Ian … of course.” She always thought he would grow up to look like his Uncle Chad, tall and slender with delicate features and smooth skin. But he looked like his father. Not exactly but close enough. She’d heard that he’d become a doctor, which was not a surprise. As much as she detested his father, the jerk had slept walked his way through school and still gotten straight A’s. At least Ian has more sense than Bradley. Or perhaps it was less arrogance?

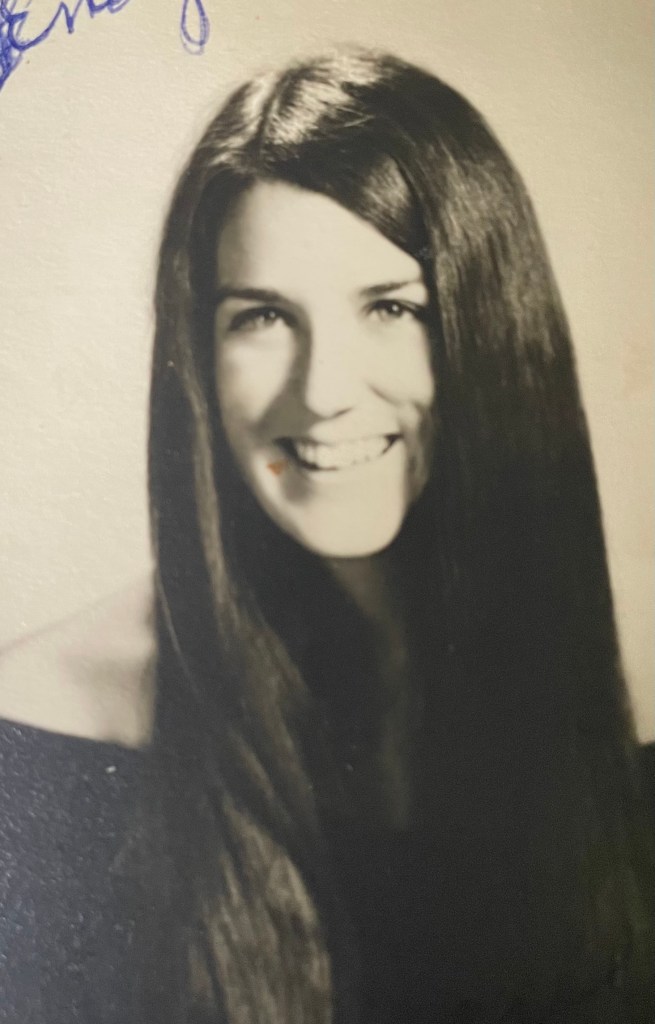

“And that’s my daughter Angela.” He pointed to the trio of preteens crowding a table where crackers and cheese and veggie platters were spread. Two of kids were short and stocky with curly brown hair and ruddy complexions. The third was tall and thin with aquiline features and creamy white skin. “The tall girl with long black hair?”

“Yes.”

“She’s the spitting image of your mother at that age.“

“Aye, she is. And she’s artistic as well. ”

“And her mother?”

“We’re divorced.”

“Oh.”

“It was amiable. She didn’t like Alabama and that’s where my residency was.”

“Oh.” An amiable divorce. Imagine that. Nora had never talked about her children in the same way as other parents might. Were they happy adults or were they suffering? Did she get along with their spouses? Sandy had no idea.

Their attention turned to the images now being projected to a screen on stage. All of the benches set up for viewing purposes were empty, except for the woman running the slide projector. She wept as Nora appeared coyly in the woods, followed by Nora defiant on a mountain ridge, Nora mellow next to her lake and so on. Always staring into the camera as if to say: “There is nothing you can do to hurt me now. All the magic has died and I’ve bled out.”

They watched in silence. It was not the memorial of a life but another art installation.

“You know, your mother always told me she’d die before she reached forty and in a way she did. She went to that place in Marin and became Leonora.”

“Ah yes Leonora. You have to remember that, by the time Mom turned thirty-eight, Iris and I had left town. Iris had moved to Alameda and and I’d joined the army. So she was free. No more kids to take care.“

“I hadn’t seen your mother in so long that I was really, really surprised to get the invitation. And, a phone call from Iris.”

“Mother specifically requested that Iris track you down and persuade you to come. She said when you saw her final pieces, you would understand — Oh God she’s on the move.”

“What?”

“Dorothea’s coming in this direction. She’s had a few strokes you know. If you’re lucky she might not remember who you are.”

“Dorothea?” She turned and sure enough. The grande dame of the Seagrass clan had risen from her seat of honor amongst the mourners and had aimed her walker directly at her grandson. “I heard that Katie moved back into the River House and is taking care of your grandparents.”

“Yes.”

“Nora said Katie was a saint.”

“Did she?” Ian glanced at his watch and then back at his grandmother. “I think it’s time to check in with my service. Listen, we caught a break. It looks like Dorothea’s spotted another soul who needs saving.”

“My cue to leave as well.” She’d circled the art exhibit three times, stopping in front of each piece to take in Leonora’s disturbing visions: men with wolf-like eyes ripping the clothing off prepubescent girls and raping them with long barbed tongues. Witch doctors gleefully ripping babies from their mother’s wombs, beheading them and dropping the remains for hyenas to feast upon. All this on twelve foot high rolls of butcher paper in vivid oil pastels — violets, neon greens and blood red crimsons. (At one time, blue had been her color.) Every corner, every edge of her canvases was filled with pagan symbols. In the end, Leonora decided to leave no breathing room.

“Do you know why Mother wanted you to see her final pieces?”

“Yes, I think I do. There’s a face in each of the pieces, generally in the background … It’s been so long but … yes, I think I understand.”

“The face of my father?”

“No,” Sandy chuckled. “Nor is it Chevy. Although I ran into him and his sister in the parking lot and he told me all about Alison. Gads, it’s only been a couple of months.”

“So you can understand why it’s hard for me to come back to Reno as well. Chevy thinks he martyred himself and now … well he’s full of justifications.”

“Yup, he is.” She worried that Ian might ask about the face his mother had repeatedly placed in the background of her horrific scenes but he just nodded. Perhaps he knows the story, she thought, perhaps he’s heard it many times before with that special twist that only years of Seagrass religiosity can add. It wasn’t a story she ever told her children. It wasn’t a story for children brought up to believe that the Devil didn’t exist and that good could overcome evil. However every October when the weather changed and the fog rolled over the coastal hills, she remembered Daniel.. Everything else grew murkier over the years but she remembered Daniel.

Ian hugged her and said how glad he was to see her again and then he slipped out the entrance, passing Chevy with a nod. Why was Chevy still lingering at the reception table, she thought. He said he was only going to make his presence known and then leave? Was he waiting for her? Did he think because she understood how difficult life with Nora could be she would absolve him?

Praise the Lord and pass the biscuits! She remembered that the banquet hall had a back door.

Renwick Ruin – and excellent place for an Art Exhibit.

A fascinating start to this story, Jan. I’m very curious about Daniel and Nora.

Thanks Robbie – I have the rest broken down in much shorter pieces.

🌈💗

I’m all ears…

Great story, JT. The Jesus is Number One piece and the oil pastel by Connemoira are incredible.